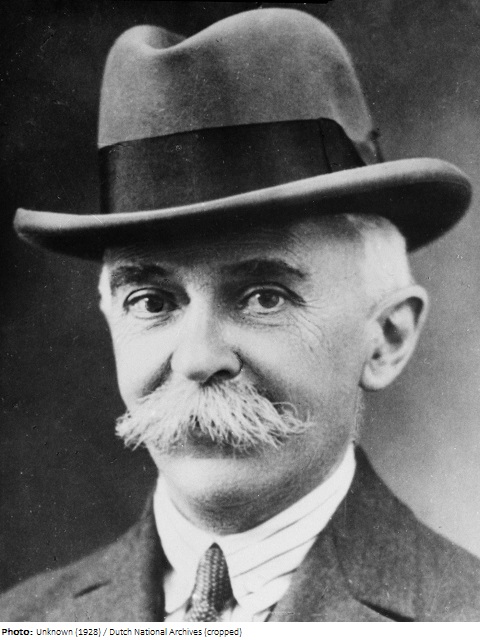

Pierre, Baron de Coubertin

Biographical information

| Roles | Competed in Olympic Games • Administrator |

|---|---|

| Sex | Male |

| Full name | Charles Pierre•Frédy de Coubertin |

| Used name | Pierre, Baron•de Coubertin |

| Other names | Georges Hohrod, Martin Eschbach |

| Born | 1 January 1863 in Paris VIIe, Paris (FRA) |

| Died | 2 September 1937 (aged 74 years 8 months 1 day) in Genève (Geneva), Genève (SUI) |

| Title(s) | Baron |

| NOC |  France France  Germany Germany |

| Medals | OG |

| Gold | 1 |

| Silver | 0 |

| Bronze | 0 |

| Total | 1 |

Biography

Pierre, Baron de Coubertin, served as the 2nd President of the International Olympic Committee, but his importance in the Olympic Movement far overshadows that simple statement. Although recent scholarship has shown that he was not the only person who had the idea to begin international Olympic Games, he is certainly the person still mostly responsible for the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. For this effort, he is correctly termed le rénovateur.

Born in Paris as Pierre Frédy on 1 January 1863, he was descended from a noble line that had lived in France for over 500 years. After his preliminary studies he entered law school in 1884 although he never intended to practice law, and he left after one year, enrolling instead in the École libre de sciences politiques. Coubertin had early on decided that his goal would be the reform of the French educational system. He based this reform on ideas he had gleaned from visits to England, observing their educational system, the first of which occurred in 1883.

From England, Coubertin learned of Thomas Arnold’s theory about the principal element in English male education: sports. Arnold had become headmaster of Rugby School in 1828 and, although not an innovator in teaching methods, his aim was to reform Rugby School by making it a school for gentlemen. Coubertin studied his system of school sports, student self-government, and post-graduate athletic associations, and hoped to incorporate them into the French educational system.

During the 1880s school sport competitions started in Paris. For the first time, high school students played football (soccer). Shortly thereafter, the Racing Club de France was founded, with Coubertin as an officer of the club. In 1888 Coubertin published the results of his studies on the British educational system, which were more or less a reflection of Arnold’s theories. Coubertin next formed a committee designed to be responsible for physical education in schools. The committee was mostly run by Coubertin, but found little support among the French public.

In July 1889 Coubertin traveled to the United States and Canada to visit several universities, colleges, and high schools, to examine the structure of North American educational systems and sporting organizations. On his return Coubertin traveled again to England where he met William Penny Brookes, who had started a series of sporting festivals in rural England, which he called the Much Wenlock Olympian Games. From Brookes, Coubertin also learned of a series of sporting festivals in Athens, termed the Zappas Olympic Games.

Spurred by these findings, and hearing of multiple archaeological discoveries in ancient Olympia between 1875 and 1881, Coubertin became enthralled with the idea of re-establishing the Olympic Games as a modern international sporting festival. In studying the ancient Olympics, Coubertin thought that at least one reason for the flowering of Greece during the so-called Golden Age had been sport and the ideal of the Olympic Games.

In November 1892 Coubertin organized a conference at the Sorbonne in which he discussed the history of sports and the possibility of renewing the Olympic Games. At this conference he made his now famous proposal, “Let us export rowers, runners, and fencers; there is the free trade of the future, and on the day when it is introduced within the walls of old Europe the cause of peace will have received a new mighty stay. This is enough to encourage your servant to dream now about the second part of his program: he hopes that you will help him as you have helped him hitherto, and that with you he will be able to continue and complete, on a basis suited to the conditions of modern life, this grandiose and salutary task, the restoration of the Olympic Games.” But his message fell on deaf ears. There was no support for the idea in France in 1892.

Coubertin refused to give up. He arranged another conference at the Sorbonne for June 1894, this time inviting a more international gathering of delegates. The theme of the conference was ostensibly to discuss the role of amateurism in sport, but Coubertin secretly had planned to broach the idea of reviving the Olympic Games once again, a topic which he added to the end of the program, and he was finally successful. The delegates voted to re-establish the Olympic Games as an international sporting festival, and to begin the festival in 1896 in Athens. In addition, the conference formed the International Olympic Committee to oversee the Olympic Games.

Coubertin felt that the President of the IOC should reside in the nation hosting the next Olympic Games, thus he established Demetrios Vikelas in the post. With the 1900 Olympic Games scheduled for Coubertin’s hometown of Paris, Coubertin took over as President of the IOC in 1896, and remained in the post until he voluntarily resigned in 1925. For those 29 years, he was the International Olympic Committee, and the Olympic Movement. Most of the philosophy of Olympism, the structure of the Olympic Movement, and many of the major ideas of the Olympic Games came through him. He had little help, as an Executive Board to assist him in decisions was not formed until 1921. In addition, much of the money used to run the IOC, and publish material related to the committee and the Olympic Games, came from Coubertin’s personal fortune. Sadly, he greatly depleted this fortune in the effort, and struggled financially in the last years of his life, as did his widow, who survived him by over 30 years.

Coubertin published copiously during his lifetime, and wrote extensively on the idea of the Olympic Games and the Olympic Movement. Much of the philosophy of Olympism is derived from his writings, although Coubertin defined that philosophy in several different ways. For him, it consisted of internationalism, fair play in sports, and sport for all. Modern sports scholars consider that Coubertin envisioned the Olympic Movement as a peace movement, attempting to bring together the peoples of the world in peaceful competition.

Coubertin’s ideals formed the modern Olympic Movement, except for his attitude towards women in sports. He never supported the idea at all and resisted allowing women to compete at the Olympic Games. Fortunately, the IOC changed this dramatically after he stepped down as President in 1925.

Coubertin moved the headquarters of the IOC to Lausanne, Switzerland in 1915, living there until 1933 when he settled in Genève. After the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris, he never attended another Olympics. But at Berlin in 1936, his voice was recorded and his famous statement concerning the Olympics was announced to the crowd of over 100,000 at the Opening Ceremony, “The important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part. Just as in life, the aim is not to conquer but to struggle well.”

Coubertin’s personal life outside of the Olympics was not nearly as successful, and it is possible that later in life he used the Olympic idea as an escape from his troubles. In 1895 he had married Marie Rothan, the daughter of family friends, and they had several happy and successful years, but their later years were marred by the sad fates of their children. The first-born, Jacques, suffered mild brain damage after his parents left him in the sun too long when he was a little child. Their daughter suffered emotional disturbances, never married, and never found peace in her life. Marie and Pierre de Coubertin blamed each other and tried to console themselves with two nephews who became substitutes for their own children, but the nephews were killed at the front in World War I, ending the ancient Coubertin line with the death of Pierre de Coubertin.

Pierre, Baron de Coubertin, le rénovateur of the modern Olympic Games, died while walking in a park in Genève on 2 September 1937. He was buried in the Bois de Vaux in Lausanne, almost within sight of the present IOC headquarters, but per his wishes, his heart was removed from his body and buried near the site of the Ancient Olympic stadium, where it had always beat.

De Coubertin won the gold medal in literature under the pseudonyms Georges Hohrod (FRA) and Martin Eschbach (GER), both names of neighboring villages of the home of his parents-in-law in Alsace. From 1871 until the end of World War I, Alsace was part of Germany. Seven years after the Stockholm Games, he himself admitted this fact. He submitted the poem Ode au Sport in German and French. Even today historians speculate who wrote the German text, because de Coubertin was not fluent in German.

Results

| Games | Discipline (Sport) / Event | NOC / Team | Pos | Medal | As | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1912 Summer Olympics | Art Competitions |  GER GER |

Georges Hohrod, Martin Eschbach | |||

| Literature, Open (Olympic) | 1 | Gold |

Organization roles

| Role | Organization | Tenure | NOC | As | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| President | Comité national olympique et sportif français | 1894—1913 |  FRA FRA |

Pierre, Baron de Coubertin | |

| Member | International Olympic Committee | 1894—1925 |  FRA FRA |

Pierre, Baron de Coubertin | |

| President | International Olympic Committee | 1896—1924 |  FRA FRA |

Pierre, Baron de Coubertin | |

| Honorary President in Perpetuity | International Olympic Committee | 1925—1937 |  FRA FRA |

Pierre, Baron de Coubertin |

Olympic family relations

- Granduncle of Geoffroy de Navacelle

List mentions

- Listed in Olympians With Asteroids Named After Them (2190 Coubertin)

- Listed in Olympian Members of the Nobility (Baron)

- Listed in IOC Members of the Nobility (Baron)